Why Glencore bought Israeli tycoon out of Congo mines

Group distances itself from Dan Gertler after he was implicated in bribery

Ivan Glasenberg, left, Glencore chief executive, no longer

has Dan Gertler, right, as a business partner in

two DRC copper mines

Glencore’s announcement last month that it would pay $534m to Mr Gertler to buy him out from their shared prize assets in the DRC — two giant copper mines — is designed to insulate the London-listed mining cum trading behemoth from the fallout of a widening corruption investigation involving the Israeli businessman, say people who have followed the saga.

The decision by Ivan Glasenberg, Glencore’s chief executive, highlights the risks of doing business in the resource-rich, war-torn central African country, where Mr Gertler wields influence by virtue of his close friendship with Joseph Kabila, the DRC president.

Settlement documents released in September by US authorities in a scandal involving Och-Ziff, the New York hedge fund, alleged that an “Israeli businessman” — whose description clearly matches Mr Gertler — had paid bribes to Mr Kabila in order to obtain special access to mining rights in the DRC.

One banker who does dealmaking in the mining sector and owns Glencore shares says the company’s purchase of Mr Gertler’s stakes in the two DRC copper mines is defensive. “Buying out Gertler is primarily about detoxification for Glencore,” he adds. “The Och-Ziff investigation in the US has made it very risky to have clear ties to him.”

Shareholders also say it makes sense for Glencore to buy out Mr Gertler from the two mines, partly because of the Och-Ziff case. Mr Gertler has denied wrongdoing, and says his efforts to bring billions of dollars in investment to the DRC deserve a Nobel Prize.

The Financial Times has established a paper trail that shows how Glencore helped Mr Gertler maintain his shareholding in one large copper mine in the DRC — and how the Israeli went on to use that stock to raise funds for what US authorities say was a bribery scheme. The trail weaves through opaque offshore havens and the world’s leading mining bourses.

It begins with a takeover battle nine years ago, waged well before Glencore’s blockbuster initial public offering in London in 2011.

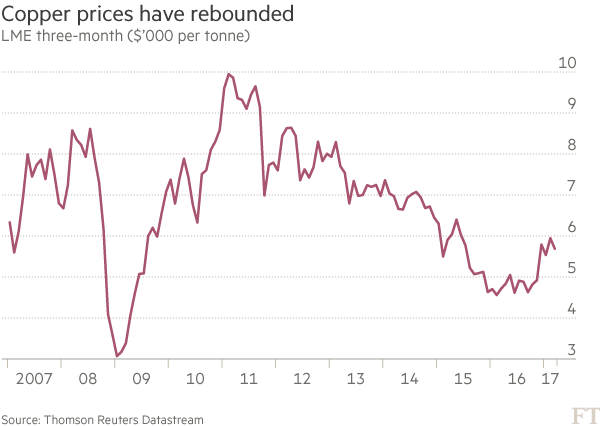

In late 2008, Toronto-listed Katanga Mining was on its knees. It controlled one of the planet’s highest-grade copper deposits, in the DRC’s Katanga province, but prices for the metal had tumbled. In the thick of the financial crisis, no one would lend the company money — except Glencore, which under Mr Glasenberg was hungry for high, and sometimes risky, returns.

Glencore’s largesse came in the form of a $265m loan to Katanga Mining in January 2009 that could be turned into stock.

With Katanga’s share price having collapsed, when Glencore converted the loan into equity, it amounted to a takeover. The other shareholders were all but wiped out — except Mr Gertler, whose interests the Swiss group’s actions helped to protect.

Mr Gertler at Katanga Mining's operations in 2012

Mr Gertler had built up a significant minority stake in Katanga Mining, and Glencore’s “loan-to-own” arrangement would have heavily diluted his shareholding.

But instead, Glencore issued a loan of $45m to Mr Gertler in February 2009, which was channelled through Bermuda and the British Virgin Islands and enabled Mr Gertler to preserve his shareholding in Katanga, according to corporate records.

Glencore made no such loan to other Katanga shareholders. Its loan to Mr Gertler emerged only in 2014 when the campaign group Global Witness was leaked the paperwork.

By the time of this loan in 2009, Mr Gertler and Glencore had already had shared ownership of a mining business in the DRC — and the Israeli was well known as a controversial figure in the country.

As far back as 2001, UN investigators probing the role of the mining industry in funding civil war in the DRC had pointed a finger at Mr Gertler. They reported that, in exchange for a monopoly on trading the country’s diamonds, he had supplied the then-president Laurent Kabila with funds to buy weapons. Kabila was assassinated that year and succeeded by his son Joseph, with whom Mr Gertler had struck up a friendship.

Mr Gertler embarked on a string of secretive mining deals in the DRC that deprived the country of $1.4bn in potential revenue, according to a 2013 report by the Africa Progress Panel, an advocacy body chaired by former UN head Kofi Annan.

Joseph Kabila, president of the Democratic Republic

of Congo

Mr Gertler has used an array of offshore companies to amass his interests in the DRC. The BVI-registered vehicle he used for the Katanga Mining transactions with Glencore was called Lora Enterprises Limited. Its name would crop up again, last year, in a corruption scandal that has humbled one of New York’s leading hedge funds.

In September, Och-Ziff, a fund with $39bn under management, paid $413m in fines to US civil and criminal authorities after admitting complicity in bribery in five African countries. The fund and the authorities released an agreed account of Och-Ziff’s misconduct. The section on the DRC made uncomfortable reading for Glencore.

The US prosecutors’ account states that, between 2005 and 2015, an “Israeli businessman . . . paid more than one hundred million US dollars in bribes to obtain special access to and preferential prices for opportunities in” Congo’s mining sector. It goes on to describe loans from Och-Ziff to the Israeli that were allegedly used, in part, to pay bribes.

The descriptions of two of the unnamed recipients of the alleged bribes indicate they were President Joseph Kabila and his late right-hand-man, Augustin Katumba Mwanke.

The description of the Israeli businessman’s dealings makes it clear the source of the alleged bribes is Mr Gertler. His representatives said: “We dispute all accusations of wrongdoing in any of our dealings in the DRC including those with Och-Ziff . . . We dispute any allegation of bribery.” The DRC government also rejected the allegations and praised Mr Gertler’s commitment to the country.

Och-Ziff executive Michael Cohen

According to the Och-Ziff settlement documents, in November 2010, Michael Cohen, the London-based executive who ran the fund’s African operations, emailed a subordinate to say that “[Mr Gertler] has asked for a margin loan on katanga shares which want u to handle”. Mr Cohen, who denies US civil charges of corruption, was referring to the significant minority shareholding in Katanga Mining that Glencore’s $45m loan had enabled Mr Gertler to maintain.

Within two weeks, Och-Ziff had sent $110m in credit via the Cayman Islands to Mr Gertler’s Lora Enterprises Limited. The same day, Lora repaid Glencore’s $45m loan, plus interest. Then, it appears from the Och-Ziff settlement statement, Mr Gertler is alleged to have used some of the remaining money for bribes, including four payments in eight days totalling $7m to “DRC Official 1” — Mr Kabila.

Glencore stresses that, unlike other mining companies, it did not secure its entry into the DRC’s vast copper belt through a deal with Mr Gertler, but rather ended up in business alongside him when they independently acquired interests in some of the country’s mining assets. The Swiss group accepts that it has helped Mr Gertler financially, but says its involvement in a string of offshore transactions that culminated in the alleged bribery by the Israeli ended well before any illicit payments were made.

Glencore said: “The loan that Glencore made to Lora was used by Lora in 2009 to fund its participation in a convertible loan to Katanga, which was ultimately exchanged for shares in Katanga. The loan was on commercial terms and was fully secured over the Katanga shares. The loan was fully repaid to Glencore in 2010, at which point the security was released. Following the release of the Glencore security, Lora was free to dispose of the Katanga shares or to use them as security for further financing.”

A spokesman for Fleurette, Mr Gertler’s group, declined to discuss the transactions involving Lora but said that, because the company had bought its initial Katanga Mining shares before their value collapsed, it had suffered an overall $190m loss on its dealings in the stock. He added the two mining operations in which Fleurette was an erstwhile shareholder with Glencore “have generated $3bn in tax for the people of the DRC”.

Last month, Glencore said it had bought Fleurette’s 10 per cent stake in Katanga Mining. Glencore also purchased Fleurette’s 31 per cent stake in the other shared DRC copper mining venture, called Mutanda Mining.

The stakes were valued at $960m, but Glencore deducted the value of loans it had issued to Fleurette to help finance the two copper mines’ development, plus interest. This meant Mr Gertler received $534m in cash from Glencore.

Glencore now owns all of Mutanda Mining, and 86 per cent of Katanga Mining, and its increased ownership of the two assets gives the group greater exposure to copper, which is viewed as one of the most attractive commodities in the mining industry.

Glencore has not entirely cut its ties with Mr Gertler. He will continue to receive tens of millions of dollars in royalties each year from Glencore’s copper deposits under a deal with Gecamines, the DRC’s state-controlled mining company. However, his royalty rights at Katanga Mining are unlikely to bring in much: they expire in 2019, not long after the asset, currently closed for an upgrade, is due to restart operations.

Additional reporting by David Sheppard and Neil Hume in London

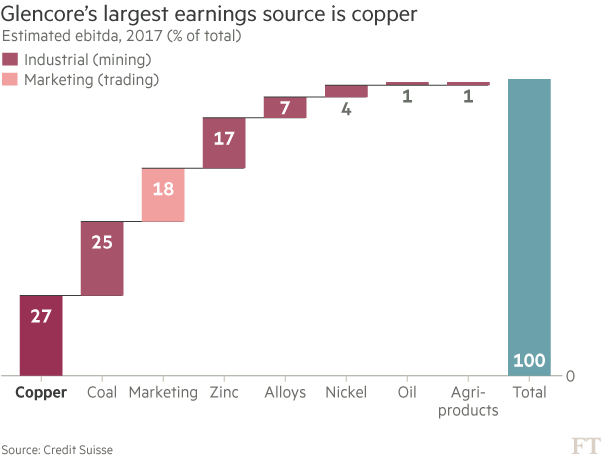

Glencore is one of the world’s bigger copper miners Glencore may be best known as a commodity trader, but the Swiss group is also one of the world’s biggest producers of copper, a key industrial metal.

Last year, Glencore’s copper mines in Africa, Australia and Latin America generated about one-third of the group’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation — making them the single biggest source of profit.

Copper is used in everything from household wiring to power grids, and is closely followed by the financial community because of its status as a barometer of the global economy.

Including its share of joint ventures, Glencore expects to produce up to 1.4m tonnes of copper this year, about 6 per cent of global output.

That figure will rise in 2018 when the company restores production at two key copper assets: its Katanga Mining operations in the DRC and deposits at Mopani in Zambia.

The two assets were taken offline amid the commodity slump in 2015 that unleashed a debt crisis at Glencore, and these African operations are currently undergoing efficiency overhauls.

Richard Wilson, of industry consultants Wood Mackenzie, says Glencore’s Katanga mining operations in particular will be a “transformed asset”, capable of producing 300,000 tonnes of copper each year, once a new $437m processing system is up and running.

Glencore will be able to extract more cobalt, a byproduct of copper mining that is used in the batteries that power mobile phones and electric cars. “Glencore have got themselves a long life, low cost mine,” says Mr Wilson.

Neil Hume in London

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017.

No comments:

Post a Comment